Writing Your Life as The Hero’s Journey

You want to create your memoirs or autobiography. You want to write about your life, but it seems like a series of unrelated incidents, random events happening one after another.

However, If you look closely, you can see where certain choices and decisions were the key points where your life diverged from one path to a different one. Each of these “inciting incidents”, to use a fiction-writer’s terminology, had a profound effect on you in one way or another, but at the time, you didn’t see them or the effect they’d have on your life’s journey.

The Hero’s Journey is a formula for writing fiction that was identified and codified by Joseph Campbell. It’s the basis for any number of novels, short stories, movies and television series, and its primary focus is on character transformation. No matter how good the plot, readers won’t connect with the story unless it has compelling, memorable characters, and a compelling character must grow, develop and change throughout the story. (There are a few exceptions, but for the most part, this is a fundamental tenet of good fiction — and memoir.)

From Wikipedia:

In his 1949 work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell described the basic narrative pattern as follows:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

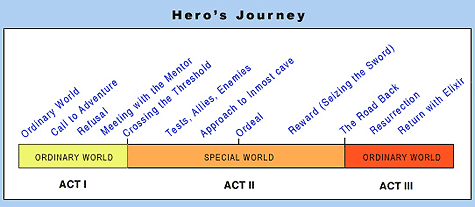

There are twelve distinct stages of the hero’s journey. All good stories have a strong Theme and Central Dramatic Question, it’s a good idea to model your memoir or autobiography on this outline, as it has universal appeal and provides a coherent framework for you.

Here are the twelve stages of the Hero’s Journey:

Act One

1. Ordinary World

This is the Hero’s day-to-day life, before his adventure starts. He has no idea of what’s to come. It’s his safe place. We learn about our Hero, his strengths and weaknesses, current beliefs and outlook. This is where we first learn to identify with him so that we can empathize with his trials later on.

1a. Ordinary World in Memoir

In life, the Ordinary World represents our comfort zone, the life of the familiar, our area of complacency. In memoir-writing, it’s a good place to start, as it gives us a chance to introduce ourselves and give some background and history. It’s important to give the reader some backstory, but we must beware of too much Telling and not enough Showing. Just because a scene is expository, doesn’t mean it can’t be compelling.

2. Call To Adventure

The adventure begins. The Hero receives a call to action. It may be in the form of a threat to him or his family or friends, his community or other allegiance. It may seem quite insignificant or merely curious, or it may be traumatic, but it disrupts the complacency of his everyday life, presenting a challenge that must be addressed.

2a. Call To Adventure in Memoir

The Call to Adventure represents change and a disruption of the normal routine. The decisions we make here determine the rest of the story.

3. Refusal Of The Call

Our Hero may be excited by the call to action or he may be frightened. He’ll have to decide whether to take up the challenge or ignore it in favour of the familiar. He still has fears, second thoughts or doubts. He resists accepting the quest and questions everything.

On the one hand, it’ll be fun, exciting, something different. Is he up to it? On the other hand, the challenge may seem overwhelming. Maybe the familiar feels far more attractive than the unknown adventure ahead, or maybe he feels unprepared, incapable or unworthy.

He’s forced to make a critical decision. If he chooses the path of apparent safety, he’ll refuse the call, accept the status quo and forever remain in the ordinary world with its illusion of security. The result of this refusal may end in some kind of suffering for him and those close to him.

Ultimately he must make the more difficult choice and embark on the adventure despite its danger and uncertainty.

3a. Refusal of the Call in Memoir

Despite the excitement implied by the challenge, it’s possible that our own response would be refusal, even denial. In fiction, the reluctant Hero’s questions, self-doubts and dilemma further our empathy with him. In memoir, even if the exact questions are different, our own self-doubt is a mirror of his. We share his emotions. We can relate to his situation. Our reader needs to share the same emotions with our story. We are the Hero of our own story.

4. Meeting The Mentor

At this crucial point, the Hero desperately needs guidance. He may not want to rush blindly into the unknown, and seeks the experience and wisdom of someone who has been there already. He meets a mentor or guide who gives him something he needs: confidence, insight, advice, training or support that helps him to overcome his fears and face the start of the adventure. He could be given an important object or talisman, insight into the challenge he faces, advice, practical training or self-confidence.

The Mentor may be a physical person or an object; a map, a book or an artifact. The Hero may learn he possesses an Inner Mentor, a strong code of honour or justice to guide him through the challenge. Whatever the Hero acquires from the Mentor, it dispels his doubts and fears and gives him the strength and courage to begin the quest.

4a. Meeting the Mentor in Memoir

In writing our life stories, we’ve all had people who influenced our decisions and helped us to make choices. It may have been one person or several; a parent, a teacher, a boss, doctor or friend. It could have been a book, a movie or television show which changed our lives, or it could have been an accumulation of self-studied information from a number of different sources which, when put together, gave us new courage, determination, insight or direction. Whether it was one single source or a coming together of coincidental information, this insight represents the Mentor in our own Hero’s Journey.

5. Crossing The Threshold

At this stage, the Hero must confront an event that forces him to commit to entering the unknown, from which there is no turning back. It could be outside forces, financial circumstances, physical disability, illness or danger of another kind. He may be leaving home for the first time in his life or just doing something he’s always been scared to do. He’s finally committed to the Journey, whether it be physical, spiritual or emotional. He may go willingly or he may be pushed kicking and screaming, but either way, he commits to crossing the Threshold between his familiar, comfortable world and the unknown.

5a. Crossing The Threshold in Memoir

Whatever this event may be in our own story, it will re-establish the Central Dramatic Question that propels the story forward, directly affecting the protagonist, raising the stakes and forcing some action. Outside forces like war, crushing poverty or political enemies may push the protagonist to answer the call, or the push could come from internal forces such as PTSD, determination to find a birth parent or a commitment to overcoming an illness or disability. These forces help establish the question which drives the entire narrative.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies

Having crossed the Threshold, our Hero must face an increasingly difficult series of challenges that test him in a variety of ways. He has to learn the rules of this frightening new world. Physical challenges or people determined to thwart him crop up repeatedly and must be overcome.

This stage is our first encounter with the Hero’s new environment. Here we learn how its conditions and inhabitants contrast with his Ordinary World. The Hero needs to find out who is trustworthy and who is suspicious. He may find allies, meet a sidekick, or assemble an entire army.

He may run into enemies whose opposition will help prepare him for even greater trials. His skills and abilities are tested and his commitment to the Journey is challenged. He questions whether he can succeed and every obstacle that he faces and overcomes gives us deeper insight into his character. Ultimately we identify with him even more.

6a. Tests, Allies, Enemies in Memoir

As we move further into our story, we write about the challenges we faced and overcame. We identify the people and circumstances that helped us, and the ones that set us back. We learn to navigate the rules and regulations surrounding the journey towards the culmination of our personal quest. We may have needed to learn a new language, become familiar with legal precedents or figure out how our diet impacted our endocrine system. Each time we met a new challenge, or ran into a roadblock we or our allies acquired new knowledge or new partners to help us keep moving forward. Each time we did, our self-knowledge deepened and we became stronger and more self-aware.

Act Two

7. Approach To The Inmost Cave

The Hero is adjusting to his new situation and now must go on to face the main challenge, the inmost cave. This is the place where his opposition or enemy is strongest and where he must succeed in order to find and secure the object of his quest. The approach focuses the Hero and forces him to prepare for the ordeal. He will need to use everything he’s learned so far on the Journey. It also binds his allies more strongly together and rededicates them to their mission.

This Threshold is often much more treacherous than the first one. Once again, the Hero may be forced to step back and take some time, facing his fears and questioning the wisdom of his decisions. Up ’til now, he’s been able to avoid dealing with an inner conflict or flaw which could derail the entire endeavour, but he and his allies are now too invested in the quest and too close to their destination to go back. It’s the point of no return. He must face his inner demons and find the courage to proceed. This moment of reflection helps the reader to understand the gravity of the coming challenge and ramps up the tension and anticipation of the impending ordeal.

The reader’s assumptions about the Hero and his allies are overturned as each character displays new qualities under pressure, but despite their new-found dedication and courage, they are soon brought to bay. All seems lost. A major obstacle blocks the way forward. It could be a trap, imminent defeat, a breakdown in strength or communication, or it could be some other roadblock which looks as if it will stop the quest permanently. All hope appears lost.

In this moment of greatest despair, the Hero accesses a hidden strength, faith, energy or creativity and he accesses a power or ability he didn’t know he had.

7a. Approach To The Inmost Cave in Memoir

In life, we each have had moments when we felt we couldn’t go on. We’ve given it all we’ve got but the challenge was just too hard. But there is always something, some inner strength or purpose that kept us going. Perhaps it’s determination to care for someone else, a child, a parent, and we tell ourselves that quitting simply isn’t an option. Perhaps it’s pushing through a tangle of bureaucratic red tape that seems determined to stop our progress. It’s this point in our story that we find an inner strength to keep going for one more minute, one more day, one more challenge.

8. Ordeal

This is the final test. It’s the supreme, life-or-death crisis which determines the ultimate fate of the Hero and his world. He may be betrayed by a treasured ally or have a long-held core belief destroyed; he may find himself entirely alone to face his enemy. He must face his greatest fear, his deadliest antagonist, and he must employ all of the skill, strength and experience he’s gained throughout the Journey. Everything he stands for, everything he loves is on the line. Fail now and everything is lost.

The Hero must experience a type of death and resurrection in order to overcome this greatest challenge. Only through death, either real or metaphorical, can the Hero be resurrected with greater power and insight.

The suspense for the reader is unbearable, wondering if the Hero will prevail.

8a. Ordeal in Memoir

This is the stage where you must face your biggest challenge. It’s the point in your story where you are most outside your comfort zone. You could be dealing with a diagnosis, challenging a legal ruling, taking a final exam which will determine your future, going to a critical audition, meeting with a publisher, signing divorce papers, or any one of thousands of huge decisions or challenges. The whole story has led up to this point.

Every life is different and what may be the ultimate challenge for some, may be ho-hum for others. The memoirist must face this challenge having transformed in the previous stage. His new insights help him to overcome this ordeal.

9. Reward (Seizing The Sword)

The Hero has gained the quest’s objective and has become the hero he was meant to be. The objective may facilitate the Hero’s return to the Ordinary World. It may have been physical — a magical elixir or object of power; it could be wisdom — a secret, great knowledge or insight, an epiphany or moment of clarity; it could be emotional — a reconciliation with a relative, friend or ally, a romantic connection with a lover; or it could be courage — overcoming or learning to live with disability, defeat or illness.

However, the actual, physical reward is secondary, compared to the internal transformation experienced by the Hero. After cheating death, he may discover that he has gained clairvoyance or intuition, profound self-realization or a moment of divine recognition.

He is changed by his experience and has earned a celebration before the Journey resumes. This allows him to replenish his energy and lets the reader catch their breath before the Journey reaches its ultimate conclusion.

9a. Reward in Memoir

The memoirist has achieved a great victory or success. His choices have been vindicated, proven effective or correct. He’s battled government and won. His disease is in remission. He’s escaped from imprisonment, found a soulmate or won a court battle. This is the point in the story where he can take some time to be introspective, reflect on his success and evaluate his growth over the course of the narrative.

Act Three

10. The Road Back

Now that the Hero has achieved his goal, he must return to the Ordinary World. This stage is a reversal of the original call to adventure in that the Hero, who has become adept in the Outside World, must return to ordinary life. Because he’s changed, on his return he may be acclaimed, praised, vindicated or exonerated by those he left behind. Alternatively, they may not comprehend the extent of his ordeal or even value the sacrifices he endured for their sake. He fears he may not fit any longer. He’s become accustomed to a life of adventure.

His success may make it difficult to give up the Outside World for an ordinary life, so he must make a choice between his own preferences and the greater good. He needs a push to force him onto the road back to the Ordinary World, so he can resolve whatever issues remain.

At this stage, an event happens to give him that push. The Event may be an external force or an internal decision that must be made by the Hero. In either case, it heightens the stakes and reinforces the Central Dramatic Question. If the hero has not fully resolved the issue with his adversary or opposition, it comes after him with a vengeance in a last-ditch effort before being vanquished forever.

Every story needs a moment to acknowledge the hero’s resolve to complete the quest and return home with the elixir in spite of the remaining challenges. This is the scene when he secures all that he’s learned, stolen, or been given and sets a new goal.

10a. The Road Back in Memoir

The goal having been achieved, the memoirist must go back to a more normal life. He feels a sense of accomplishment. It’s finally over. He’s been fighting so long, he’s forgotten what normal is, so it may be necessary to reflect and define what the new normal may be.

At this point in the story, something gives him an insight into what to do next. It might be meeting a new person, deciding to share his story in a significant way, helping someone in a similar situation to the one he’s overcome. It could be a sudden reminder of his former danger, but it must relate to the overall question which drives the story.

He embarks on a new life, a regimen of health, learning new skills or a new language and culture, makes an effort to meet people, generally re-learning to live normally, using the skills and knowledge he’s acquired throughout his journey.

11. Resurrection

This is the climax of the story. It’s the final dangerous confrontation and the hero must be shown to have transformed, using all the skills and lessons he’s learned in order to overcome the enemy on his own, with minimal help from his allies.

The danger is usually at the at the highest intensity of the entire story and the threat has grown to encompass the entire world, not just the hero. The stakes are at their very highest. The hero and the reader have reached the highest level of awareness, emotional intensity, catharsis and release.

This is the point at which a plot twist will have the most impact — an unexpected event which changes the entire outcome of the story.

11a. Resurrection in Memoir

One last time, the memoirist must face his challenger. Perhaps a disease returns, a spouse dies, his home is destroyed or lost, or his enemies find him. This is the final climax, the point at which he ultimately succeeds or fails. If he wins through, he can go on with his normal life. If he loses, he loses everything.

12. Return With the Elixir

The hero’s transformation is now complete and he returns to the ordinary world with the elixir. This can be a new understanding to share – love, wisdom, freedom or knowledge, or it could be something physical – a great treasure or artifact. Something must be brought back from the ordeal in the inmost cave. Otherwise, this hero or another is doomed to repeat the adventure.

Above all, the Return stage must satisfy the reader. They have followed the Hero throughout the story, empathized with him, related to his challenges and experienced his adventures. It’s important that their questions are answered in a realistic, believable manner.

The Return is the endgame of the story where all subplots and story questions are resolved. Subplots, usually based on secondary characters, should also be resolved unless they are to be the focus of a sequel. Each character should end up with some variation of elixir or learning. New questions may be raised, especially if there is to be a sequel or the story is part of a series, but all old issues must be addressed, all open loops closed.

The Hero’s return may bring fresh hope to those he left behind, a solution to their problems, new education or perspectives for them to consider. The value of the hero’s reward should mirror the value of his sacrifice, and the adversary’s payback should be proportionate to his sins.

12a. Return with the Elixir in Memoir

The memoirist has overcome the final challenge and can now return to his new life. The knowledge, wisdom and skills he’s gained throughout the adventure of his life can be passed on to others. He has the advantage now of hindsight, and can explain from a point of view of insight what happened, and why. He can show how his decisions made an impact on the lives of others, and help his descendants to understand the times he lived through.

Conclusion

In a strictly factual autobiography, it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to follow a predetermined story structure such as the Hero’s Journey in every one of its plot points, since life’s a messy business. It just doesn’t happen in a convenient, linear fashion. However, if you’re writing a memoir — a slice of life with a particular theme and message — it’s possible to craft it more like a novel, with all the rising and falling action, character development, decision points and climaxes.

However you decide to build your story, having an outline is a good way to start, whether it be Campbell’s Hero’s Journey or a different type of stostructure. Simply knowing the start point and the end point of your story can shorten the journey immeasurably. All you have to do is decide what goes in the middle!

I’m being ridiculous, of course…writing your story takes a lot more effort than that, but, like any journey, having a clear idea of your destination helps you get there faster and more easily.

Happy Writing!

2 Comments

Hillary Volk

Beverly, this is such an excellent article! I loved Joseph Campbell’s interview with Bill Moyers back in the 1990’s, and have his book, “Man, Myth and Legend.” Your review makes me want to go back and read JC’s “The Hero’s Journey,” although you have beautifully summarized it.

As soon as I complete my current manuscript, I intend to work on my own fictionalized memoir, and I will certainly refer back to your site and materials for assistance.

Beverley Hanna

Thanks, Hillary.

Are you familiar with Christopher Vogel’s treatment of the Hero’s Journey?

His book, “The Writer’s Journey” does more than any other I’ve read to clarify the separate elements, showing how and why they fit together.