Part Two — The Seven Universal Emotions

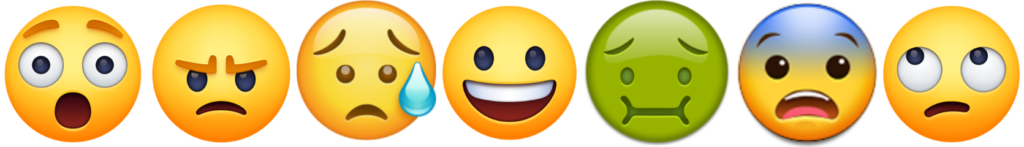

In Part One, I mentioned that, through the work of psychologist Paul Ekman, we’ve learned that there are seven main expressions common to every culture.

Emotions occur in response to some kind of stimulus (actual, imagined, or re-lived) such as:

- a physical event

- a social interaction

- remembering or imagining an event

- talking about, thinking about, or physically reenacting a past emotional experience

No matter where in the world we live, no matter how remote, we all display the same expressions for the same emotions. Even congenitally blind people who have never seen these emotions on other people’s faces spontaneously show the same facial expressions.

What Are Facial Expressions?

Facial expressions mirror our emotions. They’re the way we communicate our emotions to others, usually with some degree of voluntary control, but as previously stated, some emotions “leak” through involuntarily, despite our attempts to suppress them. In addition, our words can only go so far.

For millions of years, even before we became human, we communicated our thoughts, emotions and intentions through facial expressions and body language. It’s been estimated that 90% of our understanding of others still comes through these non-verbal communications. Because we share the same emotional states as dogs and other animals, we also share many of the same ways to express them. Baring the teeth in aggression, for example, has evolved to become a sneer in humans. Smiles also evolved from teeth-baring expressions of surprise and initial greetings.

Our faces are made up of 43 different muscles and are capable of making more than 10,000 facial expressions, but the seven main ones are:

- Surprise

- Anger

- Fear

- Disgust

- Happiness

- Sadness

- Contempt

Combinations of these emotions are also possible. And it’s the combinations that give us such a descriptive range of emotional expression for our characters.

For the next several weeks, we’ll go through the ways we express each of these emotions. For a photo of each of these facial expressions of emotion, check out https://www.paulekman.com/universal-emotions/ on Paul Ekman’s website.

This week, we’ll cover the emotion of Surprise and how we can use it in our writing.

![]()

Surprise

Surprise is caused by sudden, unexpected occurrences such as a loud sound or unexpected movement. The function of surprise is to focus our attention so we can process what is happening and determine whether we are in danger. Many types of humour rely on surprise for their effect, when the audience or reader expects one outcome and is surprised by another.

Surprise is caused by sudden, unexpected occurrences such as a loud sound or unexpected movement. The function of surprise is to focus our attention so we can process what is happening and determine whether we are in danger. Many types of humour rely on surprise for their effect, when the audience or reader expects one outcome and is surprised by another.

Some psychologists don’t consider surprise to be an emotion because it always changes into another emotion as we process the occurrence. Therefore it is the most fleeting of our normal (or macro) facial expressions, lasting only a few seconds at most. Depending on what surprised us, that expression may morph into fear, anger, happiness or other emotion, or it could simply fade if the incident that caused the surprise was irrelevant or of no significance to us.

What to Look For

The facial characteristics of surprise are:

- Eyes open wide, showing more of the white of the eye

- Pupils dilate, allowing more information to be gathered by the eyes so that we can process it faster, in the event that the stimulus indicates a threat

- Eyebrows arch

- Jaw drops

Physiological Responses

Many subtle little indicators can be recorded by lie detectors.

- A rush of adrenaline prepares the body for fight or flight

- Elevated blood pressure

- Muscular tension

- Increased heart rate

- Slightly elevated temperature

What the Character Does

What the Character Does

The involuntary bodily reaction is:

- Flinching or freezing, giving a potential predator little information on our movements, which might give away our position — the “deer in the headlights” reaction, which provides us with a moment to process the situation and decide what to do.

- Covering the mouth, perhaps in an atavistic self-reminder not to make a sound, again to give predators as little information as possible.

- A gasp or sudden intake of breath

The subsequent reaction after initial processing can be:

- No emotion if the surprising event was of no consequence

- Relief, relaxing the muscles, sighing

- Anger

- Happiness, excitement, euphoria

- Amusement, smiling, laughter

- Sadness

- Fear

- Disgust

What the Character Feels

For example, someone attempting to suppress a feeling of surprise, fear, anger or contempt in order to fool a lie-detector might deliberately cause himself pain — pressing on a wound or bruise, or a stone in the shoe in order to mask the involuntary bodily reactions and micro-expressions that could give him away.

As a micro-expression, even though we may try to keep our face impassive, we can’t entirely control our reaction. The widening of the eyes may last only a split second, but it’s there if we’re trained to see it. And the pupils expand — a subtle “tell” that is a sure giveaway. Someone suppressing this emotion might tic, twitch or tense for a moment, as they get their bodily reactions under control.

This is all part of the Action/Reaction Cycle. In a later article, I’ll cover this cycle in more detail, but basically, there’s the initial reaction to a stimulus, then cognition and processing, and then some kind of decision or action in response.

When we understand this cycle, we can use it to make our characters behave in a much more realistic manner, using the “Show, Don’t Tell” rule most effectively.

![]()

Types of Surprise and How to Use Them in Storytelling

Out of the Blue – when something happens completely unexpectedly with no warning. There’s no foreshadowing, no indication that it is about to occur. It can feel like a cheat if you don’t handle it well, so it must be inevitable and within the believability parameters of the story’s characters and situation. A “deus ex machina” rescue of the hero or the narrative is a cheat for the reader because it violates the necessity for the protagonist to be the agent of change in the story. But the sudden appearance of a brand-new problem which adds to his current difficulties is not. There must be some relevance to the rest of the narrative and particularly to the protagonist’s character arc. Eg. “My Sister’s Keeper”, by Jodi Picoult.

Out of the Blue – when something happens completely unexpectedly with no warning. There’s no foreshadowing, no indication that it is about to occur. It can feel like a cheat if you don’t handle it well, so it must be inevitable and within the believability parameters of the story’s characters and situation. A “deus ex machina” rescue of the hero or the narrative is a cheat for the reader because it violates the necessity for the protagonist to be the agent of change in the story. But the sudden appearance of a brand-new problem which adds to his current difficulties is not. There must be some relevance to the rest of the narrative and particularly to the protagonist’s character arc. Eg. “My Sister’s Keeper”, by Jodi Picoult.

Foreshadowed Surprise – This surprise is one that has been hinted at prior to the reveal. It’s vital that your foreshadowing is subtle, so that the surprise, when it comes, is truly a surprise. You don’t want your reader guessing it beforehand, but you do want them to think, “Oh, I should have seen this coming,” because the hints and clues you sprinkled about ahead of time led to this inevitable conclusion.

Exceeding Expectations – Wikipedia says: “Chekhov’s gun is a dramatic principle that states that every element in a story must be necessary, and irrelevant elements should be removed. Elements should not appear to make “false promises” by never coming into play.”

This means that when you write an element into a story — an object, a joke, an animal, an incident — it must be significant in some way. The rifle must be fired, the joke told, the animal or the incident figure in the action somehow. But if you exceed the reader’s expectations, you could have this element show up repeatedly. By using the element as a symbol, for example, it could represent something intangible, a black cat could represent impending danger, a mirror might represent a relationship between characters, and so on. When you use these elements unexpectedly and more frequently, you can create expectations in your reader. You can satisfy their anticipation and move beyond them to things they hadn’t expected or even considered.

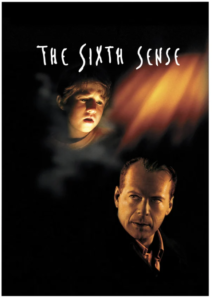

Twist – The Surprise Twist is entirely based on context and interpretation. It only feels like a surprise because the reader has been carefully prepared to reach a different conclusion, so when the twist is revealed, the reader is surprised, but can instantly see that their interpretation led them to a different answer. Twists are harder to pull off, but when they’re done well, there is a powerful sense of satisfaction in the reader because throughout the story, up until the twist, they’ve been accumulating evidence that points in a different direction to what they’ve assumed to be true. Clues that seem to mean one thing actually mean something else. Red herrings help to conceal the truth, right up until the big reveal. Eg. The movie, “The Sixth Sense” with actor Bruce Willis.

Twist – The Surprise Twist is entirely based on context and interpretation. It only feels like a surprise because the reader has been carefully prepared to reach a different conclusion, so when the twist is revealed, the reader is surprised, but can instantly see that their interpretation led them to a different answer. Twists are harder to pull off, but when they’re done well, there is a powerful sense of satisfaction in the reader because throughout the story, up until the twist, they’ve been accumulating evidence that points in a different direction to what they’ve assumed to be true. Clues that seem to mean one thing actually mean something else. Red herrings help to conceal the truth, right up until the big reveal. Eg. The movie, “The Sixth Sense” with actor Bruce Willis.

Twisted Tropes – This surprise relies on your reader understanding the tropes or standards of the genre they read regularly — the action hero saves the day, the separated couple finally reunites, the detective solves the case. Within each of these conclusions, there are steps that the reader expects to happen — in a romance, there must be some force that keeps the pair apart, there is usually some misunderstanding or secret that separates them, there is yearning, first kiss, first sexual encounter, more separation, often social pressure, bias or prejudice, familial disapproval, war, distance or misinterpretation of motives.

Since your reader expects these things, they think they know how the story will turn out. A good trope twist will surprise them with something they didn’t see coming, which makes the story more memorable. Or possibly a disaster if it’s mishandled.

Check out tvtropes.org. This site covers all the tropes in all the genres, sub-genres and sub-sub-genres. It’s a real time-suck, but a whole lot of fun.

![]()

For the next several weeks, we’ll explore each of the Seven Universal Expressions Of Emotion. In the next post, we’ll cover Anger.

Happy Writing!

If this information is helpful useful or simply interesting to you, please leave a comment below and let me know. I’d love to hear from you.

Related Posts:

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.

3 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback: