Writing Groups – Getting Your Muse on Track

Joining or Setting up a Writer’s Accountability Group

If there’s a writing group in your area, you can ask to join. There are so many benefits to being part of a group of like-minded writers — camaraderie, skills development, brainstorming and support. Some groups are exclusive, but many are not, so it’s worth inquiring. If you can’t find one to join, you might consider starting one of your own.

In last week’s article, I wrote that I’d post some guidelines you can use to start your own writers’ group. Once you’ve found another writer (or several), before you begin you must decide what will be the focus of your group.

Types of Writing Groups

Social Groups

Many writing groups are simply social clubs – a non-judgmental place where people get together to share discussion, conversation and a love of writing. In this type of group, there may be little focus on genre or development of the craft of writing. The intent is camaraderie, support and encouragement, social interaction and the opportunity to network with other writers.

For professional writers in this type of group, discussing the marketing and professional aspects of the publishing industry tends to dominate: cover design, agents and editors, digital vs. print, self- vs. traditional publishing, query letters, competitions, etc.

Alternatively, those who are not interested in publishing could use a group like this for conversation about craft, skills and styles, though often the topics can veer away from writing entirely.

Alternatively, those who are not interested in publishing could use a group like this for conversation about craft, skills and styles, though often the topics can veer away from writing entirely.

However, Caveat Scriptor…

The members of this type of writing group, particularly where the emphasis is on memoir, tend to become very close friends, because so much of what they write about is extremely personal. The result is that they tend to be open and vulnerable with other members, so beware: A single injudicious remark or thoughtless criticism could cause irreparable pain, especially to an author without a lot of confidence.

If there are forceful people in the group with strong opinions, they may inadvertently cause strife or even the breakup of the group by polarizing certain individuals in the group against others. It’s not fair for one member to try to impose their own style, morals or values on the rest of the group, so it’s probably best to leave politics, religion and other emotionally-charged topics out of the discussion.

Support or Accountability Groups

The focus of accountability groups is on helping members get their writing done. By meeting regularly, they offer a committed deadline and a forum for members to showcase the writing they’ve done each week or month, depending on frequency. Writers read and share what they’ve done since the previous meeting. Often the group will write about a specific prompt or topic, or require a specific word count. It’s a way to get members past the blank page, procrastination or writer’s block. Though this is not strictly a critique group, the group’s feedback can serve as a kind of pre-edit, particularly if other members have enough experience to help pinpoint problem areas in the work before the member sends it off to an editor.

This type, coupled with the social aspects of the Social Group type, tend to be the most common type of writing group found in seniors’ organizations.

Writing Practice Groups

These groups often comprise writers who need a push or an organized way to schedule writing time. The main activity is writing, usually to a deadline. Writing sessions shared with other writers can be extremely productive because it forces members to focus exclusively on writing and ignore all other distractions. Generally, no phones, kids or even conversation is allowed to intrude on these creative sprints. It’s a great way for writers to make regular, dedicated appointments so they can focus on their craft when life keeps intruding on writing time.

This type of writing session is usually timed, so everyone knows how long they have to work, and are either in-person meetups or online forums. Having a hard deadline creates a strong momentum to get the work done, only later considering whether it’s good, bad or indifferent, since it can always be fixed in the editing.

This is the principle behind National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo, when writers around the world log into the nanowrimo.org website during the month of November to post their daily word count. NaNoWriMo’s goal is for participants to finish the rough draft of a novel, 50,000 words in 30 days. There’s no reason why you couldn’t apply this discipline to writing your memoir.

Workshop Groups

Some writing groups are built around a series of workshops where the focus is on the development of craft, skill and technique.

Often cost is a factor with these types of organizations, as they’ll frequently bring in visiting authors to teach a particular aspect of writing craft for which they are well-known.

Often cost is a factor with these types of organizations, as they’ll frequently bring in visiting authors to teach a particular aspect of writing craft for which they are well-known.

This type of group is particularly helpful for new writers, since they help members develop their talent and grow their confidence by learning the “how-to’s” of getting words down on paper. If there is a group of this type in your area, it’s worth the investment in time and money to join, as there is always something new to learn about writing.

Critique Groups

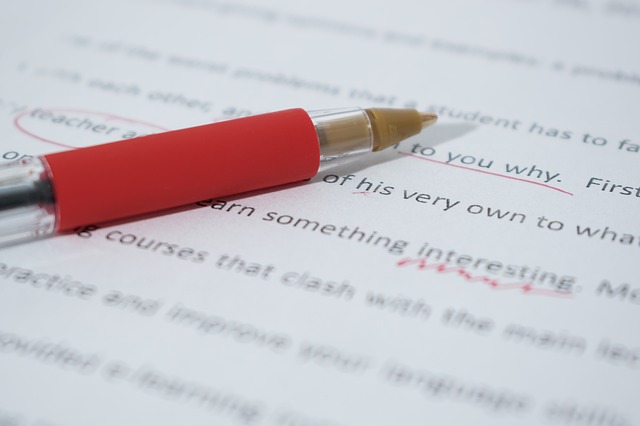

Critique groups are generally more formally organized than the other types. In this type of group, writers are asking the other members to read their work and tell them what’s good or what’s bad and why they think so, what’s confusing, where there are holes in the story, how they think it could be improved, what they’d like to see more of, and so on. It’s based on the concept of “two heads are better than one”.

Admittedly, there will be critique aspects in the other groups, but generally speaking, this group exists specifically for the purpose of improving its members’ manuscripts prior to publication.

Usually, a manuscript critique is requested by a writer after all members have had a chance to read the finished piece, so they can assess the work in its entirety. Alternatively, a specific number of pages can be submitted to the group for critique at the next meeting.

Usually, a manuscript critique is requested by a writer after all members have had a chance to read the finished piece, so they can assess the work in its entirety. Alternatively, a specific number of pages can be submitted to the group for critique at the next meeting.

A critique is not a discussion. It’s a learning experience for the writer — a way for the author to gain insight into the work from more objective minds. See the bottom of this page for a bonus checklist: “Critique Group Etiquette”

It’s about the work, not the writer

While the members critique the work, the author should simply take notes, not defending, explaining or filling in background information. The point is to discover if the work stands alone, on its own merit. Once the critique is done, the writer can then ask for clarification of critique points but should try to be objective.

Writing is a very personal endeavour. It’s easy to get defensive when we feel as if our “baby” is under attack. Our hearts and souls go into those words we put on the page, and when we are vulnerable enough to share them with others, sometimes the slightest criticism can feel like a body blow.

One-on-One – Accountability Partner or Writing Buddy

One of the most stimulating and rewarding types of accountability a writer can have is a regular one-on-one relationship with another writer. This type works very well when both writers are of similar skill levels. It allows them to really open up to another like-minded person, brainstorming ideas and process which is great fun and stimulates the imaginations of both writers. Often these partnerships result in collaborative works.

One of the most stimulating and rewarding types of accountability a writer can have is a regular one-on-one relationship with another writer. This type works very well when both writers are of similar skill levels. It allows them to really open up to another like-minded person, brainstorming ideas and process which is great fun and stimulates the imaginations of both writers. Often these partnerships result in collaborative works.

Final Words

The boundaries between these different types of groups are very fluid. Most writers’ groups have aspects of all of them but whichever type of group you join or create, it’s important that everyone knows and agrees to the guidelines which govern the group. If everyone is aware of and adheres to the rules, the chances of disappointment and strife are drastically reduced, and the rewards of joining a writing group far outweigh those outcomes.

Writing is such a solitary pursuit that joining or starting a writing group is a no-brainer. The opportunity to network with other writers can be the single catalyst that builds you an empathetic and understanding support system, creates for you a trusted circle of new friends and even kick-starts your writing career. Go for it!

Critique Group Etiquette

How to Critique

(and How NOT to Critique)

Though the following list applies specifically to Critique Groups, good behaviour, dignity and clear group guidelines are a necessary part of any social situation and apply to all the types of groups mentioned above. Be considerate, respect the other members’ time and opinions. Don’t be rude, argumentative or unkind.

If your group has a leader, that facilitator should ensure that each participant has equitable opportunities to participate in group discussions. No one individual should dominate discussions to the detriment of other members.

Attendance:

If you can’t make it to the meeting, let the group know well in advance. This is particularly true in cases where the meetings take place in private homes, as the homeowner takes care to clean and prepare snacks in advance.

Be on time. It’s not fair to show up late, interrupting someone else’s critique time if you expect your own uninterrupted critique.

Submissions:

Submit your work well in advance of the next meeting in order to allow all members time to review it. Depending on how long each member has for guaranteed critique time, a page limit can be imposed. Stay within that limit. Alternatively, a time limit can be determined at the beginning of the meeting, based on the expected total time of the meeting divided by the number of members requiring critique time. (Eg. 2 hours / 6 members = 20 minutes each)

Print or Digital:

To save money, a digital copy can be sent to each member via e-mail (or Dropbox for longer manuscripts). However, if a member wants a good critique, it’s helpful to print out copies for the other members so they can take their time and make notes. This has the added advantage of saving the writer time during the critique, as she would not have to take copious notes of the discussion.

The group should determine ahead of time the number of pages, usually no more than three, double-spaced, 12-point type, for an ongoing critique of a work in progress.

Guidelines for Authors:

Leave your ego at the door. It’s not about you or how brilliant you are. It’s about the work and how to improve it. Don’t bring your work for critique if you don’t want to hear honest comments about it — especially what’s wrong with it.

Leave your ego at the door. It’s not about you or how brilliant you are. It’s about the work and how to improve it. Don’t bring your work for critique if you don’t want to hear honest comments about it — especially what’s wrong with it.

Bring your best work and avoid relying on your group members to correct obvious problems. Pay attention to their suggestions and do the necessary work, so that the next time you ask for a critique, you don’t repeat mistakes they’ve already pointed out (see list above).

You aren’t obligated to take the advice or incorporate suggestions, but sometimes just hearing them can help you vastly improve the quality of your work. Be open to other viewpoints.

Don’t argue or defend the work. You’ve asked your critique group for their opinion. Listen to it, thank the members and then decide if you’ll use the suggestions.

Reciprocate. Be willing to help the other members of your group to improve their writing by critiquing their work when they ask.

Guidelines for Critiquers:

Critique the writing, not the writer. Be as objective as possible. It’s always good to start with something you like about the piece — poetic wording or lovely phrasing, compelling characters, vivd description or action scenes that kept you riveted and wanting more.

Explain your perceptions of the work and why you feel as you do. What emotions do you feel? They may not be what the writer had in mind.

Be specific about what works, what doesn’t, and why. Remember, the purpose of critique is to improve the piece, so comments like “It’s great” aren’t helpful. The reason why you think it’s great can help the writer to understand and build on that success.

Any thoughts or reactions you have could be valuable to the writer. Trust your instincts and first impressions. You never know when a remark you make could spark an idea that vastly improves the story, or so devastates the writer that they lose confidence and quit.

Criticism can feel threatening and sound like an attack if poorly phrased, and people generally tend to focus on negative comments more than positive ones. Always respect the other group members and be careful to keep your comments constructive, even if you don’t like the work or the author. Opinions differ and that’s okay. Just be authentic and sensitive to the author’s vulnerability and desire to improve.

![]()

Here’s a short list of wins and errors to look for when critiquing. There are many more, but these are a good place to start.

List of “wins” to look for:

- Lovely word choice or turn of phrase

- Great imagination

- Compelling, easily-identified and fully-motivated characters

- Good story construction — logical and satisfying narrative flow

- Easily visualized descriptions

- Believable dialogue

- Satisfying resolutions or endings

- Anything that resonates with you and why — emotional resonance, nostalgia, the shock of recognition

- Deft use of showing vs. telling — body language, physical interaction, facial expression, incorporating the five senses

List of errors to look for:

- Places where you’re confused

- Places where you find yourself bored or losing interest

- Places where there’s too abrupt a transition from one scene to another

- Head-hopping — switching points of view

- Switching tenses — past, present, future

- Too much or too little description

- Too much or too little action

- Spelling and grammar errors

- Too much repetition of words, phrases

- Telling vs. showing — as a reader, you need to feel the emotion in the scene or the character, not watch dispassionately from a distance

- Flat, dull, inconsistent or poorly-motivated characters

- Characters that can’t be told apart from one another

- Poor structure and plotting

- Unbelievable or implausible coincidence, especially if it resolves the story arc

- Anachronisms and pieces that just don’t fit

Happy Writing!