Ground your Reader with Sensory Description

We all know that it’s important to immerse our readers in our story in order that they experience it fully, but how do we do that?

“Show, Don’t Tell” is a truism that writers cannot avoid. We hear it everywhere, but what does it mean; how does it work? Engage your reader, say all the great writers; readers must lose themselves in the story. But how can we do this as writers ourselves when we don’t know how our favourite authors have done it for us as readers?

One way, (though not the only way) is through clear sensory description.

If we remember that a story should always be based on a logical succession of events, and that cause and effect govern the relevance of each chapter, scene, paragraph and sentence, then it naturally follows that the way we experience things physically also has a bearing on the outcome of events. How we feel about things emotionally and how we react physically to stimuli affects the actions we take, and it’s those actions that affect the end result.

Writers must learn to write from the heart, from the gut and from the senses in order to make their stories realistic.

When I was a painter, I used to do photo-realistic animal and wildlife portraiture. It was critical to be aware of every tiny nuance of colour, shading, shape, size and relationships in order to create a painting that was an accurate representation of the individual animals I portrayed. The way I write stories follows essentially the same process.

You can find my painting process for this painting of Labrador puppies HERE.

First, I’d do a quick sketch of the idea, like a story premise. I’d then rough in an underpainting — no colour, just the general outlines of where things might go — the first draft. Then I’d adjust for the overall composition (in writing, that would be the underlying structure, the developmental edit). Then I’d start filling in with the broad strokes and main colours, which is where many painters stop. (In storytelling, that would be rough chapters and scenes, sequences, and bringing in the element of cause and effect.) Then I’d go back and do a detailed polishing: define edges, tweak the colours, make sure the gradients are right. At this point, I’d put it away for a day or two. When I came back to it, I would stand back and look at the whole thing, noticing where the values were off or missing, highlights needed punching up, edges needed clarifying. Finally, I’d put a gloss finish on everything to make the colours pop. In writing, this would be the final copy proofing and formatting.

Now, when I write a story, I do it the same way, from bottom to top, large to small. Broad strokes through several iterations down to the details.

So, how do you write a scene this way?

For the first draft, you do your story underpainting. Write about the event — the situation and what happens. Then, write about the surroundings, the setting.

Don’t just describe a static scene. Don’t just write about some guy standing on a shoreline and leave him there. Add in the mood, the emotions and feelings of the character. Write about the waves thundering and hissing on the shore, draining back and sucking the sand from under his feet.

Write about the wind blowing through the treetops of the forest behind him, their branches lashing the sky, rustling, roaring and concealing the sound of whatever is approaching — the critical clue that your hero’s desperate to hear. Write about the way that same wind shoves his wet clothing against his body, raising goosebumps and making him shiver. Write about his confusion, his fear and how they affect his actions, how he jerks as he hears the snap of a twig, nearly missed under the roar of the wind in the trees, how he turns, ever so slowly, to face his worst fear…

And so on.

Creating a believable scene isn’t that hard. You simply need to imagine it as if you were there with the character. Imagine it as if you were taking a photograph — no — as if you were filming a movie, complete with motion capture. You need to see it clearly, in all its detail. You need to see and feel all the sensory input that a person would feel in that situation and then build on it.

Remember, we have five physical senses. Address all of them. You can take things out later, but it helps to know what the scene is like in its entirety, so you know later on exactly what to take out and what might be relevant to the action and the plot.

Start with the basic scene:

A guy standing on a beach. Good start for your first draft.

Then go through each of the senses in turn…

- Sight: This sense is what most writers rely on to describe their story world, but it’s not the only one, and we need to remember to use the other senses. What does your character see in front of him? Describe it. What might he not see behind him or to the sides? In his peripheral vision? Is it still? Is it moving? How is it moving? Describe it.

- Sound: What does he hear? What does he NOT hear that he should? If there’s a conversation, what is the tone of the dialogue? Does he hear voices in his head and can you use them as inner monologue? Does he have ringing in his ears? Take a moment and just listen to all the sounds you normally ignore. What do you hear?

- Smell: What can he smell? What’s the dominant scent? Are there nuances that might provide further clues or information that you can use in this scene or later on?

- Taste: Sometimes, a character’s mouth may be very dry, from fear or drugs, or something else. What does that taste like? Does he feel sick? Is there a lingering taste of something he’s eaten or drunk lately? Can he use the sense of taste to find out some information?

- Touch: When it comes to writing scenes that immerse a reader, this is the second most important of our senses, and is often neglected by writers. Describe the temperature of the air or water. How does that affect the body? What happens physically when we are afraid, happy, surprised, in pain? What does it feel like to have a headache or have to go to the bathroom really badly? When you touch something hot or cold, rough or smooth, wet, dry, sticky or slimy?

For each scene, do your own body check to discover what your character is experiencing. Run through each of the senses, one by one, as if you were in the scene yourself so you can build up a sensory awareness of your character’s surroundings. What is his mood and how does that affect his physical senses and awareness? What does he see, hear, feel, smell and taste? Which of these sensations has a bearing on his actions and reactions?

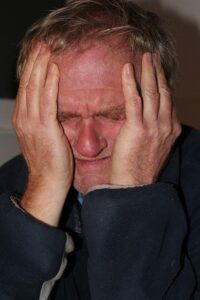

- And finally, Emotion: Emotion doesn’t happen in isolation. Emotion happens in layers — cascades of different types and degrees of emotion. Anger isn’t just anger. It also comprises fear, resentment, rejection, justification, shock, rage and a thousand other possible permutations. And it doesn’t arrive full-blown; it escalates over time; it subsides and changes. Just as you’ve explored the five physical senses to unlock the immersive experience for your reader, do the same with the emotions your character experiences. If you can unearth the mix of emotions he feels, the actions he takes will be more believable and immersive for your reader.

The more you can include sensory description in your story, the more your reader will feel he’s inside the scene, experiencing it all, along with the character.

And that immersion is the holy grail of great writing, the un-put-downable goal we all strive to reach as storytellers.

Happy Writing!

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.

One Comment

Pingback: