What Were You Thinking???

More often than not, when writers start writing about a subject, we have no clue what it is we plan to say.

“I write to find out what I think.” ― Stephen King

“I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.” — Joan Didion

Sure, we can put together an outline that gives us a rough roadmap, but until we actually sit down and start the ideation process, we can’t possibly know what our thoughts are until we have them on the page or screen in front of us. Only then can we pick them apart and look for nuggets of ideas that might be even more intriguing or important than the original concept.

The process of choosing words, forming sentences, paragraphs and scenes or chapters forces us to think logically, as we decide to include some thoughts and discard others. Writing helps us to make decisions based on what’s on the page, rather than attempting to capture and decipher the whirlwind of thoughts scrambling around in our minds.

Step One: Establish the Controlling Idea

Creating an outline can help organize things, but it’s the spewing out of a bunch of crappy ideas that gives us the building blocks to create more well-thought-out concepts and conclusions. Without those scribbles, we have no foundation, and our thoughts just chase each other around like demented squirrels until we give up in disgust. They’re just inchoate what-ifs and maybes swirling around in our heads, with no real connection to each other or to a central idea.

And it’s that central idea that is the glue that pulls everything together.

It’s also important that we know for whom we’re writing the story. A story, memoir, article, newsletter or blog post is a conversation with a friend who shares our interests. It’s not going to appeal to everyone, and that’s just fine.

We could think of it as going to a party or social gathering with people we know well. When we arrive, we automatically gravitate toward the conversations that interest us. Our readers do too, so naturally, we write for those who are interested in what we have to say and ignore those who aren’t.

But we can’t just vomit out a bunch of unconnected ideas and toss them in the general direction of our reader, so our first step is to scribble a bunch of vaguely-related ideas we think might interest them until one controlling thought begins to coalesce. We can do this using mind-maps, list-making, voice recording, or brainstorming with another writer, a mentor, a writers’ group or a coach.

Step Two: The “Vomit Draft”

Next, we need to rewrite these ideas and partially-formulated concepts and turn them into something worthy of being read. This is where outlines and revisions come in.

When we have a bunch of scribbles that are more or less in the same conceptual ballpark, we can begin to organize them into a rough outline, putting them together in a sequence that illustrates and focuses the central core concept — the controlling idea.

In order to lead their readers through the story or argument to the correct conclusion, many writers use index cards or post-it notes to shuffle their ideas around until they begin to flow in a logical sequence.

Starting with the end in mind can really help focus our work. It might help to begin with a working title that encapsulates the main idea holding the piece together. This provides an anchor that helps keep our thoughts on track.

Jot down each idea as its own paragraph, scene or chapter, and explore the secondary ideas and tangents contained within it. At this point, we’re not concerned with grammar, sentence structure, spelling or punctuation. We’re just roughing out the ideas. Some of these ideas will be dead ends, but some will be worth expanding on and developing further.

When we’ve done that for each of our concepts, we have our first “vomit draft”, and we’re ready to start the revision process.

Step Three: Revision and Connection

“I have never thought of myself as a good writer. Anyone who wants reassurance of that should read one of my first drafts. But I’m one of the world’s great rewriters.”— James A. Michener

“The best writing is rewriting.” ― E B White

It’s been said that the best writers are the best rewriters. No good writer is ever satisfied with their first draft, nor should they be. It’s true, many writers edit as they go, so their first draft will be better than a “vomit draft”, but there are several drawbacks to that habit, the biggest being the waste of far too much time chasing elusive ideas down random rabbit holes, following ideas that don’t work or end up as dead ends, often stranding the writer in the middle of a story with nowhere to go. We may be able to use these dead ends in other stories or elsewhere in the book, but as a general rule, it’s best to simply write as fast as we can and ignore the inner demand for perfection as we follow the ideas wherever they want to take us, sometimes in surprising and unexpected directions.

The advantages of a first draft written as free association, outline or even bullet points are that it takes a lot less time and it’s easier to keep up with the ideas as they flow. And a logical flow from one idea to the next is vital. Sometimes the ideas won’t naturally flow from one to the other easily, so we need to come up with transition words or phrases that can connect them. Transitions like “therefore”, “as a result”, “on the other hand” and “to that end” help to connect concepts when a too-abrupt switch from one thought to another would be jarring for the reader.

The revision process starts to knit the pieces together in a logical chain of thought and consequence. When we have a carefully-curated sequence of related thoughts based on one central idea, we can provide our readers with a well-considered premise, story or series of events in a way that makes it easy for them to follow.

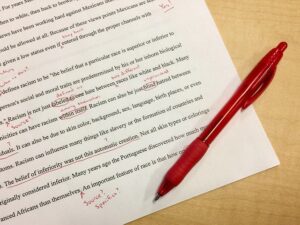

Step Four: Line Editing and Proofing

The final step is what many people think of as editing. This is going over the whole piece checking for the best word choices and phrasing (line editing), spelling, grammar and punctuation (proofreading). These aspects of the writing procedure are the icing on the cake. Too many writers do this too early in the process, wasting hours on prose they’ll never use. If we save these details ’til we’re satisfied with the content, we only have to do it once.

The final step is what many people think of as editing. This is going over the whole piece checking for the best word choices and phrasing (line editing), spelling, grammar and punctuation (proofreading). These aspects of the writing procedure are the icing on the cake. Too many writers do this too early in the process, wasting hours on prose they’ll never use. If we save these details ’til we’re satisfied with the content, we only have to do it once.

There are several online editors available to help with the final edit, among them the Hemingway app, Autocrit and my personal favourite, ProWritingAid.

A thesaurus is also a valuable aid to help with word choice.

When we sit down to write but we don’t know what to say or how to say it, we can simply use the writing process itself to help us figure out what we mean.

And, just as a bonus, writing things down also helps a lot when we have a big decision to make or an emotional situation that has us tied up in knots. We can write it out to figure out what we’re really thinking.

Happy Writing!

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.