Cause and Effect

One of the most effective ways to create a compelling plotline with a strong narrative drive is to make sure your cause and effect chain remains unbroken.

What do I mean by the cause and effect chain?

In stories, as in life, things happen because other things happen. If you fall down, you skin your knee. Your knee would not be injured if you hadn’t fallen down. That’s cause and effect.

In stories, cause and effect are a kind of glue that holds your story together. Without it, your story is merely a collection of random incidents and your reader eventually becomes bored because things happen for no reason.

All your plot elements are there because the story needs them, but as a writer, you have to provide the logic for their existence. The cause and effect chain is that logic.

The cause and effect chain idea was put forth in “Aspects of the Novel”, by E.M. Forster. In his analogy, he writes: “‘The king died, and then the queen died’, is a story, while ‘The king died and then the queen died of grief’, is a plot.”

Do you see the difference? In the first instance, the two deaths are not necessarily related. In the second instance, the queen’s death is a result of her grief, which is a result of the king’s death. Cause and effect.

Your characters all have their own agendas. Each one makes choices and decisions based on motivation. The character’s motivation is her Big Why, her reason for taking that action, based on her mood, her circumstances and her wants or needs.

Every character must have an intention or plan of action in every scene in which he or she appears, no matter how big or small that intention might be. It may be as inconsequential as deciding whether to get up and make a cup of tea, but there must be intention and motivation. And there must be some kind of opposition, even if it’s mere laziness.

For example: One character intends to leave work early (intention) so she can go talk to her kid’s teacher (motivation), whereas another character plans to rob the first person who comes out of the office (intention), so he can score his next fix (motivation).

These two intentions collide in a scene in which the addict attacks the mother, which leads to her missing the meeting with the teacher, which leads to the child’s expulsion, adversely affecting the child’s life for decades, and so on.

Opposing intentions provide the necessary components of conflict and narrative drive. The choices the characters make have consequences for themselves and others.

Sometimes the choices are small and the consequences are small — a stray thought or internal dialogue produces a physical reaction, possibly unnoticed by the character but noticed by someone else in the scene — a blush, a widening of the eyes or some other micro-expression.

Sometimes the choices are small and the consequences are huge. A man makes a tiny decision to post a silly joke or comment on social media and he ends up losing his job, or the social order is turned upside down, or the world goes to war.

How to Do It

When you’re writing your scenes, keep this causality in mind, so that your characters’ actions follow a logical path. In chronological order, write down the plot points — each of the actions that take place in the scene. Then go back and find or invent the chain of causality which provides each of them a reason for being in the scene. Make sure this chain of causality is logical and apparent to your reader.

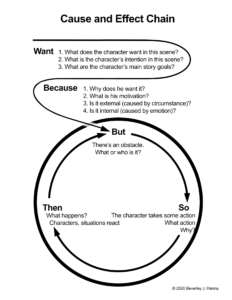

In order to help you with this, use the “Want, Because, But, So, Then” sequence — a series of questions you can ask to check the cause and effect chain:

Want

1. What does each character want in this scene, especially the main P.o.V. character?

What do they need to know, to learn?

What’s in opposition to each of these goals (conflict)?

2. What is the main character’s intention in this scene?

When the scene starts?

When it ends?

3. What are the character’s main story goals?

What are his wants, needs and weaknesses?

For the overall story?

For this scene?

Because

1. Why does he want it?

Is it external (caused by circumstance)?

2. What is his motivation?

Is it internal (caused by emotion — beliefs, values and prejudices, social and family conditioning)?

But

1. There’s an obstacle or opposition.

What or who is it?

So

1. The character (or characters) takes some action.

What action?

Why?

Then

1. What happens?

Characters react.

Situation changes.

From this point on, the story repeats the “But, So, Then” pattern. Simply follow this sequence to make sure that all of your story’s events, actions, reactions, choices and decisions are driven by causality. In this way, you can avoid the lazy writer’s fallback — coincidence. The only acceptable place for a coincidence is at the very beginning of the story. From that point on, events happen because there is a reason, even when it seems like coincidence.

When you go back through your story in order to check for cause and effect, sometimes it’s best to work backwards from the effect or outcome. Like a detective, look for all possible reasons why something happened and try to establish a logical sequence of events that led to the outcome.

Let’s use the Reedsy plot generator to come up with a basic scenario for a mystery story:

Protagonist

A freelance artist’s model who is emotionally unpredictable.

Secondary Character

A pretentious philosopher, who loves growing carnivorous plants.

Plot

It’s a family saga story about overcoming opposing backgrounds. It kicks off in an abandoned shed with a mysterious stranger approaching from the distance.

Note that: Someone in the story is struggling to live up to societal expectations.

The story starts in an abandoned shed and we need to understand how the characters got there, so we need to know something about them — who they are, what they want, what are their strengths, failings, weaknesses, emotional scars and other relationships.

The story starts in an abandoned shed and we need to understand how the characters got there, so we need to know something about them — who they are, what they want, what are their strengths, failings, weaknesses, emotional scars and other relationships.

First, we have to figure out why the protagonist finds him/herself in an abandoned shed. Next, we need to know who is the approaching stranger and why is he/she there. We need to create a plausible backstory, all the stuff that happened before our story begins.

At this point, the reader may not need to know all of this, but we do as the author of the tale. What we know impacts how we write the story, so we need to have our facts straight.

Once we know our backstories, we can work out what the opening scene is about, but until we do, we can’t know what kind of interaction these two people will have. We must understand their motives, goals, backgrounds and personalities. All of this will play into who the characters are with one another and where they fit within the story world. It affects their relationship to each other and to their respective social groups, friends, families. What they’ve done and who they’ve become in the past determines who they are now and how they’ll behave.

If we can figure out the chronology of the events leading up to this meeting, we can best decide in what order to reveal the information necessary to get the characters to that point. Parts of their histories will be relevant to the story, so at some point, the reader will need to know it too, but it shouldn’t be revealed as an info dump, especially before the reader has become immersed in the story question.

When you, the author, know exactly why your story’s events happen, it becomes easier to reveal those causes at the right time for maximum impact.

And when you do that, your reader won’t question the story’s logic or causality. They will simply enjoy it.

Happy Writing!

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.

2 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback: