Writers! Stay On Topic!

How often have you started off writing a memoir, an article, a blog post, chapter or scene and found yourself wandering off-topic, down a fascinating rabbit hole, or chasing squirrels? Your story gets off-track and lost in a muddle of ideas. You end up frustrated and discouraged because the piece is nowhere near as dynamic and insightful as it appeared when the ideas first occurred to you.

It’s easy to do when you’re in Flow, the ideas spilling out faster than you can keep up with them and you feel like a conduit for an unending outpouring of inspiration. You don’t want to leave out even one of these amazing concepts, but once they hit the page, they seem to lose their lustre. They feel confused, disconnected. Pointless.

And therein lies the problem.

Last month, I wrote about clichés and how to use them as thematic baselines for your memoir.

When you start writing, often the theme is muddy, unclear. You just know you have a story to tell and you have a need to tell it. As you write, more ideas crop up and are added to the narrative. Over time, they accumulate, and eventually, your theme emerges — that One Idea that connects everything and can be condensed into a single sentence. Often that sentence is expressed as a cliché:

- Good triumphs over evil.

- Love conquers all.

- It is better to have loved and lost, than never to have loved at all.

- When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.

One Idea to Rule Them All

One Idea to Rule Them All

It’s important to include in your memoir only those anecdotes and scenes which contribute to the One Idea.

Now, don’t get me wrong — I’m not saying don’t write all the ideas down. Not at all. But write them in the full knowledge that you aren’t going to use everything.

When you begin writing your first draft, you don’t always know what the piece is about, and it’s good to explore those rabbit holes to find the bits and pieces that can pull your story together and make it come alive for the reader.

Sometimes, it’s that one, weird, random thought that is the final piece of the puzzle. The creative process is a messy business, so getting it all out of your head is a necessary, untidy part of the experience. You need to get it into a form you can manipulate.

But if you don’t know WHY you’re writing it, you’ll end up in that muddle of ideas, chasing squirrels.

It helps if you have an inkling, right from the first, what’s the point of the story, and what’s the purpose of each scene, paragraph and sentence.

All too often, writers, particularly new writers, inexperienced writers, think that simply having written it down means they’re finished.

Oh, no, no, no! I beg to differ.

First Drafts are for Ideas

First Drafts are for Ideas

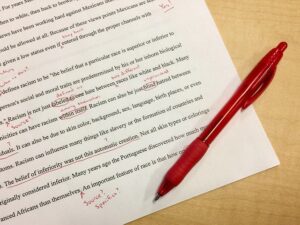

All this means is that they’ve completed their first draft, and you’ve heard me say this before — first drafts are for ideas. Subsequent drafts are for execution.

So, in order to stay on track, you must have One Controlling Idea, a theme, a point that determines what you include and what you don’t.

Without the one idea to rule them all, your work will remain muddled and full of rabbit trails — basically, a first draft.

In order to clarify the One Idea, you must repeatedly revise and edit, and keep doing so until the idea is clear not only to you, but apparent to your reader as well.

The Controlling Idea — How to Stay on Track

The Controlling Idea — How to Stay on Track

So what is a controlling idea anyway?

The controlling idea is the main idea that the writer is developing. It expresses an opinion, illustrates a concept or conveys a lesson that is important to the author.

For each separate element of your story, it helps to have a controlling idea: for the story as a whole and for each chapter, scene, paragraph, and sentence. Like the blinders on a horse that keeps him from being startled by anything that’s not directly in front of him, your One Idea keeps you from being distracted by any ideas that don’t fit your narrative.

Try to think of your story as a fractal.

- A memoir is a standalone story built around one theme or point — a single abstract idea based on universal truth, which controls the narrative. Its purpose is to share the author’s experience with the reader.

- Within a memoir, there are several chapters.

- Each chapter has one main controlling idea which is an exploration of one aspect of the main point, but on a smaller scale. The purpose of chapters is to break up the main story into related chunks or timeframes, making it easier for the reader to digest.

- A chapter requires the same elements in much the same order as the book as a whole — beginning, middle, end.

- Within each chapter, you have several scenes.

- Each scene is basically one idea illustrated by the author’s memory and experience which shows the reader one of the following changes or events: an action, a reaction, an emotional response, a realization, a conclusion, or a result. Every scene must have a change, the purpose of which is to move the story forward.

- Each scene is made up of paragraphs.

- Each paragraph’s purpose is to combine related sentences forming one idea, concept or point.

- The sentences can be descriptive, ruminative, experiential and/or poetic, but they must fit together to form one controlling idea for that paragraph.

- Sentences combine words to make up one idea.

- The careful choice of individual words defines that sentence’s single idea with exquisite precision.

When you write a memoir, it’s because you want to show your reader who you are, why you are this person and how you got that way. So you need to understand why the reader wants to know.

What makes an author’s memoir successful is its connection to the reader through their mutual recognition of its universal truth.

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.