Emotional Significance

or — How to Manipulate Your Reader’s Feelings

Over many decades of reading, I’ve come to realize that one of the most powerful things a writer can do to keep a reader glued to the page is to create a deep yearning to be in the story and experience the emotions that the story’s characters feel.

Running like an underground river beneath the needs and desires of the characters we create is the reader’s need for something only the character’s experience can provide. We read in order to become a part of the story world, to escape the everyday and immerse ourselves in an environment that satisfies something we didn’t even know we wanted.

The greatest stories, the ones that touch us most deeply, offer us something we only rarely find in real life. And to do that, we must understand some of the fundamental needs and wants that all animals, humans included, feel.

As writers, we want our characters to captivate our readers, and we’re frequently told that our characters, especially our protagonist, must have a goal and a need. All too often we pick a goal out of thin air and run with it.

But how much more effective our writing might be if we knew ahead of time what we wanted that goal to accomplish, both for the character and for the reader. How much more impact we’d have if we knew in advance how to pick the most powerfully influential goal in order to illustrate its universal human truth and leave its indelible impression on our reader.

There are several psychological models on which we could base our character’s needs and goals.

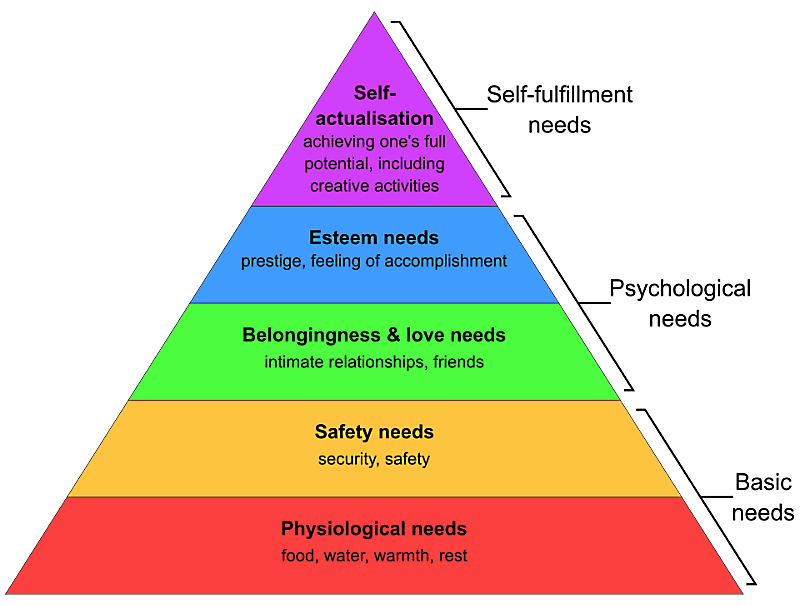

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

We could start with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which breaks down our physical, mental and spiritual requirements into a pyramid. We can’t aspire to self-actualization or creative and spiritual transformation until our basic physical needs are met. We’re too busy trying to find food, water and a safe place to sleep.

And even though this aspirational chart recognizes that we all have different levels of requirements, depending on our psychological development, it doesn’t really help us as writers. It’s a good way to examine that psychological development, but it’s a little too clinical to help with character development.

And even though this aspirational chart recognizes that we all have different levels of requirements, depending on our psychological development, it doesn’t really help us as writers. It’s a good way to examine that psychological development, but it’s a little too clinical to help with character development.

Neuro-Linguistic Programming

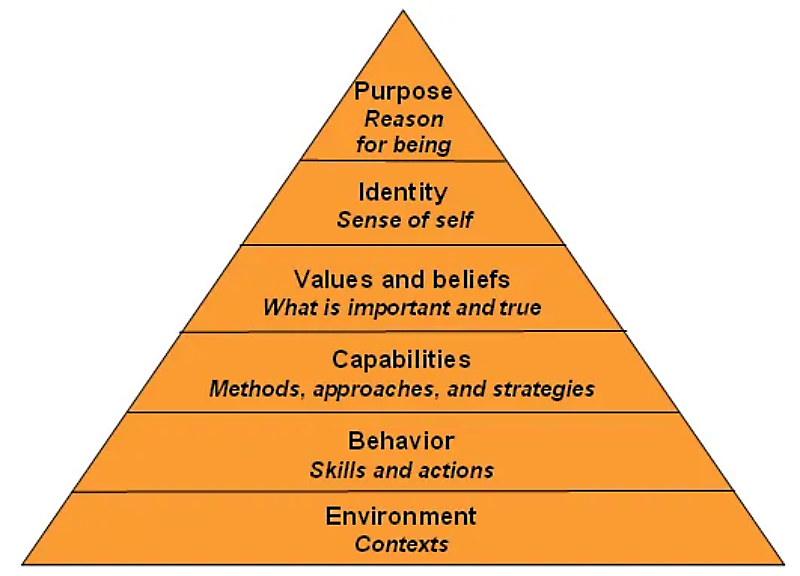

So perhaps we ought to look at the Neuro-Linguistic Programming chart for a clearer understanding of how humans work and the levels of change that we go through as we mature.

In NLP, these levels work in a similar way to Maslow’s pyramid, with each level dependent on an individual’s achieving mastery of the level below it.

NLP Logical Levels of Change

- Spirituality — What is your purpose in life? What are you here to do?

- Identity — Who are you? What is your self-definition?

- Values and Beliefs — What do you consider important? What do you expect from given situations? What is your truth?

- Capabilities — What skills do you have? What do you know how to do?

- Behaviour — What do you need to change or do?

- Environment — Where are you? What is your current situation?

NLP offers a little more wiggle-room for writers, in that these levels define more exactly the kinds of changes our characters go through in order to reach their epiphany and ultimate transformation.

You can’t change your environment unless you change your behaviour, and you can’t change your behaviour unless you first change your capabilities, and so on up the pyramid. You can’t find your true purpose in life unless you know who you are and how you identify yourself.

So how can we use these psychological templates to build a memorable and believable character?

Relate the Character’s Need to the Reader’s Desire

I think first, we need to define what we want our reader to feel — what emotions we want to leave him with when he turns the final page. So we need to create a character who experiences these feelings, because readers feel empathy with characters.

Just as we go, “aww” when we see a baby or animal do something cute, or we wince when we see someone get a paper cut, or we cry during a Hallmark moment, our readers can be led or manipulated into feeling these moments as well, but it helps to know where these feelings originate.

Just as we go, “aww” when we see a baby or animal do something cute, or we wince when we see someone get a paper cut, or we cry during a Hallmark moment, our readers can be led or manipulated into feeling these moments as well, but it helps to know where these feelings originate.

Earlier, I said that, in the best stories, readers have a deep yearning to be inside the story world. They want to be a part of the experience, whether it’s taming a dragon or falling in love, vanquishing a villain or talking to animals. These stories appease that yearning by satisfying some very deep-seated psychological and biological needs.

Different from a story’s theme, controlling idea, or abstract concept that the story’s really about, this “yearning” is the deep-down emotional need that accompanies the theme and gives it its resonance.

So, if the best and greatest stories create a deep yearning in readers, we need to identify that yearning early on. If we can recognize an unspoken, even unacknowledged craving in our readers, we can keep them hooked and reading until the end, because they won’t want to leave the story world which satisfies that craving. The subliminal contract between reader and author demands that we satisfy that craving in a way that feels right, true and inevitable.

We all want and need things, and most of those things are in reaction to our basic fears. Fear is normal and healthy, and this emotion has evolved to keep us safe, but when it takes over and begins to rule our lives, it becomes a liability.

Five Fundamental Fears

Humans have five main basic fears:

- Death or Extinction

- Loneliness or Separation

- Loss of Autonomy

- Illness or Mutilation

- Humiliation or Ego Death

Any of our other fears are variations of these five — fear of falling, fear of snakes and other phobias, fear of crowds, open spaces, even fear of holes — all stem from these basic five.

So it follows that their opposites are the yearnings and desires we all have in hopes of combating these fears. Every superhero story is the manifestation of the reader/viewer’s desire to be bigger, better, stronger, more. It’s a fundamental yearning in all of us.

Use Fear to Determine Character Goals and Desires

It makes sense for us as writers to agitate our reader’s fears through the conflicts they create within our character’s psyche.

Then we must alleviate those fears by having our characters devise innovative and effective solutions to combat them. This will satisfy the reader’s underlying yearning on a very deep, emotional level because we are alleviating the fears upon which our reader’s perception of survival depends.

When we look at each of these five fundamental fears separately, we can discover their opposites, opposites that provide the foundations of our yearnings, cravings and desires.

Our goal as writers or memoirists is to tap into those yearnings so we can keep our readers enthralled. Therefore we must identify those polar opposites so we can amplify our conflicts more effectively in the full knowledge of exactly which fear we’re agitating and what our readers want to experience.

If we can find a character’s deep-seated, underlying need for something that calms and satisfies the anxiety caused by their fundamental fear, we can help our readers feel that deep need as well, through the actions and behaviours of our characters.

So let’s examine these fears and find the yearning in each of them.

1. Death or Extinction

This fear is the basis of all religious belief in an afterlife or reincarnation and is the contributing factor in any story that relies on suspense, danger or horror to keep its readers in its grip. It’s the underlying opponent in countless stories about war, serial murderers and dystopian end-of-the-world scenarios.

The mere concept of “no longer existing” triggers a fundamental anxiety in all normal human beings. Think about how you feel when you’re suddenly scared by a loud noise, or you nearly fall off a height. This is an involuntary, visceral reaction to the possibility of not being alive. Look at all the people who’ve arranged to have their brain cryogenically preserved after their body dies, in the hope that a cure will be found for the disease that killed them.

Some deep-seated needs and desires in opposition to the fear of death might be safety, security, home, immortality, magic, faith healing, rejuvenation, reincarnation, or hope. Keeping in mind the basic fear — that of not-being — a writer can come up with ways to let the character, and therefore the reader, strive for a way to feel invincible, immortal, or eternal, or at the very least, the hope and possibility of same.

Behaviours: Behaviours opposing the fear could be changing diet, exercise routines, learning martial arts, buying a firearm, finding religion, inventing a cure for cancer or other medical research.

Examples: Jesus Christ, Robert Heinlein’s Lazarus Long, Greek, Nordic and Roman gods, healing, organ donation, the fountain of youth, or bringing back endangered species from the brink of extinction. Any story about the concept of “cheating death” and any story which includes scenes in which a character survives, especially against overwhelming odds.

Haven’t you thought about leaving your own immortal legacy, your own story for others to read, long after you’re gone?

2. Loneliness or Separation

2. Loneliness or Separation

Separation anxiety isn’t limited to human beings. It’s a part of all herd or pack animals, who recognize on a visceral level that there’s safety in numbers.

We fear abandonment, rejection, and loss of connectedness and we find safety and security in the proximity of other like-minded people. We value the connection to our tribe, our clan, and we cleave to “our people” and avoid, shun or attack others, depending on how we define their “otherness”.

We fear becoming a non-person to our tribe — unwanted, not respected or valued by others. This fear manifests itself as war, racism, segregation and discrimination.

The way another person talks, looks, behaves, what they believe, and even acceptable social distancing can determine our own behaviours, based on how secure we feel in the presence of other people. Familiarity is safe. Different is scary. Those who are considered to be different can find themselves ostracized and abandoned.

When a group imposes “shunning” on an individual, it can devastate that person. Exile from one’s country or social group causes a deep-seated fear of the changes necessitated by that exile. Not knowing who or what is an enemy creates enormous stress in individuals.

So, the yearning we might seek to impart to our characters in such a scenario is one of acceptance, connection and understanding. We want to be integrated with a group we feel comfortable with. We look for love and marriage, welcome, and adoption of similar ideals and beliefs so that we can feel part of a larger whole.

Behaviours: Behaviours a character might use to oppose or mitigate the fear could be ingratiation, false humility, co-dependence, flattery, charm, humour, self-deprecation, victimhood, altruism, generosity, buying favour, nepotism, mirroring language and behaviours, and so on. Our interactions with our peers change depending on what we perceive and believe to be important to them. We are different with our sports buddies than we are with our bosses or celebrities, and our interactions with our families are different again, depending on our status within the group.

Examples: family, friends, political parties, religion, sports, language groups, regional alliances, interest groups, businesses, clubs, associations and organizations.

How does your behaviour change with different groups? How do you tailor your appearance, language and attitude and values in order to adhere to the unspoken or explicit group norms?

3. Loss of Autonomy

3. Loss of Autonomy

This is the fear of being trapped. It’s what gives rise to our anxiety when circumstances beyond our control overwhelm, smother, imprison or control us. When it happens in the physical world, it’s known as claustrophobia, a fear of enclosed spaces, but it also extends to our social interactions and relationships. It’s also the basis of enochlophobia, the fear of crowds. In a crowd, we can be physically restricted as well as overwhelmed by the mob mentality, which may be opposed to our own normal state of mind.

Loss of autonomy often happens in situations when an individual isn’t allowed to think for himself or is treated like a cog in a machine, such as corporate settings, prisons, dictatorships or in relationships where one individual controls the behaviours of another.

In this case, the longing would be for freedom to make one’s own choices and decisions, to have control of one’s own destiny. The grass may not be greener on the other side of the fence, but it sure looks that way from here.

Behaviours: Behaviours opposing the fear of losing our autonomy could be similar to fear of separation in many ways. Depending on what’s at stake, we might fear losing a job or status, so we appease those in power or remain in toxic relationships or situations that require us to be subservient. But this only exacerbates the situation.

We may become depressed or anxious, and we may lash out at family or someone unrelated to the stressor, simply because we believe they’re safe to unload on, with the result that we destroy our own safety net. We may become violent and angry or we might internalize the stress, becoming ill. When children are overly-controlled, we see an inability to make a decision, or an overbearing narcissism when they grow up — a control freak rebelling against authority.

Others might look for a way to change the situation, overcome the restrictions or escape the constraints — quit a job, leave a marriage, dump household clutter, blow up an office building or learn how to meditate.

Examples: The Hunger Games, any romance novel that begins with a loveless marriage, school shootings, Covid fatigue and the so-called Freedom Convoy in Ottawa. Suicide or drug addiction or deliberate overdose. The Great Escape, The Shawshank Redemption.

4. Illness or Mutilation

4. Illness or Mutilation

We fear loss or damage to any part of our body. The idea of being raped or otherwise physically invaded, or of losing the integrity of any organ, body part, or natural function fills us with dread. This gives rise to phobias and anxiety about animals and insects, fear of heights or violence, and an abhorrence of anyone who exhibits such mutilations, reminding us of our own fragility. We fear any loss of physical autonomy through depletion or deprivation of our own abilities and strengths, whether it be through sickness, damage, chronic pain or age.

The opposite of this might be a desire to heal oneself or others, finding a cure for disease, addiction or mental distress, or dedication to caregiving for another person. Similar to fear of death and loss of autonomy, we fear anything that limits our capabilities or potential, so our goal or desire would be in a direction that would avoid illness or pain, or the alleviation of such.

Behaviours: Phobias about sharp objects, insects and spiders, snakes, cats, dogs, guns, fire, and heights are based on this fear of damage, illness or mutilation.

Examples: Skyscraper, Jaws, Deep Blue Sea, Snakes on a Plane, Arachnophobia, and any memoir about Paralympians or sports figures who’ve overcome amputation.

5. Humiliation or Ego Death

5. Humiliation or Ego Death

The fear of humiliation, shame, or self-disapproval is a state of mind that threatens our own sense of self, our self-identity. We fear the disintegration of our own feeling of worth, competence and value.

This fear is related to our fear of separation since we rely on the good opinion of others for our status within society. Only when we learn to trust and value our own opinions and viewpoints do we gain the confidence to dismiss the opinions of others and go our own way. Ironically, it’s this confidence which makes us more attractive and valuable, but it can tip over into arrogance all too easily.

The yearning in a character with this fear would be for the respect and high esteem of others, or an unshakeable sense of his own value, whether validated by others or not. A character’s epiphany and transformation could highlight this change of focus. Belief in one’s own worth is key.

Behaviours: Initially a character could be insecure, clumsy, unattractive or mutilated in some way, so their self-esteem is damaged. Often, a character with low self-esteem, or who thinks of himself as shameful or useless will resort to fantasizing about a better version of himself, or using self-deprecating humour to deflect what he believes to be the ridicule of others. The character’s transformation and enlightenment could be the result of new confidence in learning a new skill or a new way of being or thinking.

Examples: The Elephant Man, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Many successful stand-up comics use self-deprecating humour to put a good face on their own self-contempt.

Conclusion

When we create our characters, it’s important for us to know them inside and out, so that we can make them as real as possible for our readers. When we can give them real fears, yearnings and adaptive behaviours based on genuine psychological principles, we can truly connect with our readers, because on a subliminal level far below the conscious, readers recognize something in the character that reflects something in themselves.

And when we can satisfy their yearning on that deep, intuitive level, we’ll also have gained satisfaction — that of knowing we’ve done our job successfully.

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.