Description—How Much Is Too Much?

Don’t use a five-dollar word when a fifty-cent word will do.

— Mark Twain

What is Description?

Merriam-Webster calls it “an act of describing, specifically: discourse intended to give a mental image of something experienced.”

Or: “a statement or account giving the characteristics of someone or something, a descriptive statement or account.”

Narrative (the events), and description (how the character experiences the events), are the glue that keeps your reader stuck in your story. If nothing much happens, if the character is not emotionally engaged, then neither will the reader be engaged.

Why is Description Necessary?

1. Description is all about the strategic delivery of important information to the reader. Often, we may assume our reader is familiar with our story’s background where such familiarity doesn’t actually exist. In this case, we need to give more description in order to help ground the reader.

A well-written story depends entirely upon the writer’s observational skill and ability to imagine how characters react in certain situations. If a picture is worth a thousand words, it’s imperative that you learn to observe the world around you in order to be able to describe it clearly for a reader who has never seen, felt or smelled it.

That said, modern storytelling is a good deal less descriptive than prose which was written before the advent of movies and television. Prior to electronic media, people didn’t already have a mental library of images of what exotic locales might look like, so authors who did, had to describe them in minute detail.

Nowadays, our descriptions can be more succinct, hinting rather than providing a written photograph. Our readers are more sophisticated through exposure to stories in all kinds of media, so we must be better storytellers overall, in order to retain their interest. Our stories must be better crafted, our descriptions more focused and our characters more well-rounded.

Finding a Balance

2. Details add nuance, depth, colour and emotion to our storytelling. This means that we need to choose, not only the right details to describe but also the right amount of detail. Too much, and the reader gets bored waiting for the action. Too little and the reader loses interest because he doesn’t care.

Readers need to be able to visualize the action, setting and characters. Writers must use words to describe how the characters feel, what they see, hear, smell and touch.

Less is more. In order to maintain a reader’s curiosity, writers must keep the reader guessing. Storytelling is a conversation, a contract between writer and reader. Honour the contract and respect your reader. Leave enough unsaid that he can fill in the blanks on his own. Provide just enough detail to give your reader an anchor and trust his imagination to fill in the rest.

When you create a vivid picture for your reader, it’s easy for him to become lost in your story, imagining himself as the character, experiencing what the character experiences, the sights, sounds, textures, and emotions. He reacts as the character reacts, feels what the character feels, but it’s a delicate balance for the writer, between including too little description and too much. Better to have one or two very specific details, (like the tiny death of a crystalline raindrop as it shatters on a raspberry leaf) than many generic ones (like raindrops splashing on nearby bushes).

Descriptive writing inevitably takes more words but pays off in more vivid mental images, with the result that the reader becomes more fully immersed in the story.

Description Indicates Significance

3. The amount of description you use as a writer depends on the pacing of the scene. If it’s fast-paced, the character doesn’t have much time to experience every little detail, and neither does the reader. If it’s slower or more important, more description can and should be included.

In fast-action, character- and plot-based stories, descriptive detail for the sake of detail can be redundant and self-indulgent. There’s nothing wrong with beautiful language, but be aware that every detail slows down the pace. Poetic language may very well add to the emotional resonance of a setting or atmosphere but use it deliberately to establish that resonance, not for its own sake.

4. Use description to anchor in the reader’s mind the significance of the detail. When you use descriptive detail, it must be for a very specific reason. That reason may be to convey a feeling, atmosphere or mood, or it could be to portray emotion or action. It could be to give the reader a sense of tension, foreboding or anticipation, but if it’s just there to fill space, add to your word count, or because you’re in love with your exquisite turns of phrase, you’re probably better off leaving it out.

Purposes of Description

5. Description is written entirely for the reader’s benefit. Writers must paint vivid word images so we can create our story’s world in the reader’s mind. Description is a guide that leads him into the story and an anchor that helps him orient himself. Descriptions of setting create a sense of place and allow the reader to see where events are happening. Description also establishes atmosphere and mood.

A character would never describe something to himself in a passage of inner monologue. He might use dialogue to describe something to another character, but only as long as the other character doesn’t already know it. He must have a legitimate reason for that description. A character’s info dump would be, you’ll pardon the expression, “out of character”, and entirely for the purpose of filling in the reader. Therefore, if the character wouldn’t do it, you, the writer, shouldn’t either. Instead, determine how important the information is and if it’s critical, find other ways to convey it to the reader. If it isn’t significant, leave it out.

6. Description of characters by the author helps the reader to see who is involved in the action. This type of description helps the reader to draw conclusions about the characters based on how they’re described—how a character moves, reacts, talks and thinks, all tell the reader something about that character.

7. Description of characters by other characters also tells the reader something about both the speaker and the person he’s describing. Use descriptive dialogue to show the reader who your characters are in relation to each other.

In addition to the information content of the character’s speech, the way a character talks about another character can tell the reader a lot about the speaker. If, for example, he uses belittling or demeaning language, this tells the reader a lot about the way the speaker feels about the other person. It can also indicate his values and prejudices, his vocabulary and education and more. Likewise, praising or offering opinions on the other’s behaviour says as much about the speaker as it does about the other character.

8. Pacing: The story’s pacing will affect the amount of description you use. More description slows down the pace, less speeds it up.

Terse sentences, sentence fragments, sharp dialogue, short paragraphs, scenes and chapters, all contribute to a feeling of intensity and speed up the pace. Cut every unnecessary word and use onomatopoeic words to increase impact. Here’s where a good thesaurus can be a big help.

But your exciting scenes must be balanced with moments of quiet and introspection or they lose their effectiveness. You can use an increase in description to give the reader a bit of breathing space after a fast-action scene. As the character catches his breath and processes the fallout, so can the reader.

Adding the right details and actions can increase tension. Slowing the pace also means sharpening the focus, and as long as the focus is on something important, the reader will keep reading. Readers don’t need to know everything in order to follow your story. Give them the details that matter, and let them imagine the rest.

9. Why is it there? As a writer, it’s critical for you to identify in every scene the importance of each element of that scene and how much of your word count you want to devote to it.

Use description to indicate the significance of each item, each comment, each character, each moment of every scene. If it’s important to the plot, use more description. If it’s less important, use less. Readers will remember something described in detail better than a passing mention. Once established, your settings and characters may need only a brief reminder to spark the reader’s recollection.

For example, If your character is rushing through a setting he doesn’t really notice, it doesn’t merit much description, but if it’s a clue to a mystery later in the story, it requires more. If a character is encountering or noticing something for the first time, he’ll be more aware of details, so a more detailed description is in order. If his attention is focused on something or someone, that’s where the description should be focused as well.

How to Use Description

1. Use the description of setting to establish a mood or atmosphere. You can use subtle hints and prompts that tell the reader there may be something to fear in order to set up a sense of foreboding and reader tension. There’s no need to be heavy-handed with the description. Readers will pick up on subtlety.

2. Use description of character to introduce a new character or update changes in his situation, indicate to the reader his thoughts or opinions, beliefs, prejudices and values.

Describe a character’s first appearance enough to give the reader a picture but not so much that it slows down the action. Tell the reader only what’s necessary for him to identify this character when he encounters him later. If a character changes, that change must be described so the reader can keep up. Again, the more important a character is, the more description he merits.

Remember the writer’s adage, “Show, don’t Tell”. You can do this through dialogue, internal monologue, description of his actions, emotions, physical actions and sensory impressions and his interactions with other characters and his environment. Instead of saying “he felt frightened”, describe his physical and emotional reactions to what he sees, hears, smells, touches, tastes. This will give an immediacy to the reader experience.

3. Unless you’re using an omniscient third-person point of view, don’t describe anything the character would not know. If he doesn’t know or care about it, he would be unaware of it and unable to describe it.

4. Use original images. You don’t want your writing to sound like a cliché. Take the time to paint your own word pictures. When you describe a setting, be creative with your words, using metaphor and dynamic verbs instead of “ordinary” verbs and modifying adverbs.

For example, instead of a forgettable description like, “the waves crashed loudly on the shore”, use something like: “the waves crested, giant green monsters that paused before collapsing exhausted like a spent lover, before withdrawing, only to die again and again on the battered boulders shuddering beneath their assault.” This image, because it includes a strong emotional component is far more memorable to the reader.

5. Avoid descriptive lists. Your reader will remember isolated elements better than a list of characteristics. For example, don’t say a character had brown hair, blue eyes, a dimple and a limp. Instead, sprinkle these details throughout the story only when they’re relevant or noticed by another character. Perhaps someone mentions that his eyes are a blazing blue and a couple of scenes later, notices his fetching dimple that only appears when he’s honestly amused. This makes each characteristic more memorable/significant.

The exception to this would be if you want to hide a clue in plain sight. In that case, you could add it to a list of other attributes. The reader may not consciously remember, but subliminally they won’t forget and will recall it later in the story when it suddenly becomes significant.

![]()

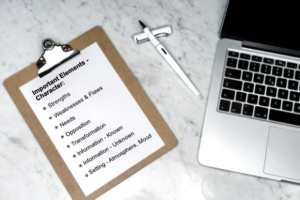

Exercise

Choose one of your own scenes and make a bulleted list of everything that’s important to this scene and to the story as a whole. If it’s important, keep or enhance it. If it’s filler, get rid of it.

Questions

Characters:

- What is the minimum the reader needs to know about each character?

- Is appearance important?

- What personality traits need to show up immediately and what can be described later?

- What information that drives the story forward does each character bring to the scene?

- What sensory information can you show the reader through the character’s experiences?

Setting, Atmosphere and Mood:

- What is the minimum amount of information the reader needs in order to feel comfortable in your character’s world?

- What details would provide that information?

- Does the setting have an influence on the outcome of the action? How? Why?

- Could another setting serve as well or better?

- What is the general atmosphere and mood of the scene?

- Can the setting be described in a way to enhance that atmosphere?

Significance:

- What information does the reader need in order to make sense of the events of the story?

- Is there an item, an occurrence, a sound, some relevant detail that could be repeated throughout the story as a symbol, clue or hint? Is there something that could symbolically represent an aspect of character or be an indication of foreboding that merits extra description?

- Is there an important hint or clue that you can hide in plain sight—included in a list or as a throwaway description with other seemingly unimportant details?

- How important is it that your reader feels what your character is feeling at any given moment in the scene? If it’s necessary, then describe it. If it isn’t, leave it out.

Pacing:

- How fast or slow do you want this scene to go?

- If it’s fast-paced, can you eliminate most of your description?

- Can you use dialogue and short, choppy or fragmented sentences and paragraphs to speed things up?

- If it’s slower, depicting serenity, mindfulness, or breathing space following a fast scene, how can you use more description, as the characters pause to take stock of their situation and surroundings?

- Can you use the specificity of your description to focus on actions or observations that increase reader tension?

When and Where:

- Early in the story, give the reader enough description to ground him in the story and acquaint him with the characters and setting. More detail can be added later.

- Go over your scene and try to determine if possible, how much you assume the reader already knows. Look for your own blind spots.

![]()

I’d love to hear how you use description in your own work. Leave a comment below and let me know and if this has been helpful to you, please tell your writer friends. Hit the Facebook icon and share the fun.

Happy Writing,

Beverley Hanna

Trained as an artist in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, I was one of the first creatives to be employed in the computer graphics industry in Toronto during the early 1980’s. For several years, I exhibited my animal portraiture in Canada and the U.S. but when my parents needed care, I began writing as a way to stay close to them. I’ve been writing ever since. I run a highly successful local writer’s circle, teaching the craft and techniques of good writing. Many of my students have gone on to publish works of their own. I create courses aimed at seniors who wish to write memoirs, with a focus on the psychology of creatives and the alleviation of procrastination and writer's block.

One Comment

Pingback: